Saving Gokyo from itself

How tourism and climate change are transforming Nepal’s most fragile and scenic places

I was born in ancient mountain ecosystem of Solukhumbu in Nepal. For me, not to be among mountains is like being without parents who look after their children and prepare them for their future.

The mountain landscape is not just the icy peaks that tower above us, but also a natural habitat in which highland people like myself live, inheriting the rich natural and cultural resources. We have borrowed it from our ancestors to live in and admire in this life, before we pass it on to future generations.

From a purely material point of view, mountains are rich in natural resources that include water, timber, minerals and rare biodiversity. They call them ‘eco-system services’. However, equally important is the healthy, natural lifestyle and rich cultural heritage of mountain peoples.

Mountains also offer a place of rest from the troubles of the world, and are a desirable destination for tourists, migrants, pilgrims, or just urban refugees who seek solitude, adventure, recreation, scenic and spiritual beauty.

For centuries, the relative remoteness and isolation of mountains protected them from human impact, and even if people used the natural resources they did so more sustainably than in many lowlands.

But with better connectivity, the combined advances in extractive resource technology and increased leisure time, both the negative and the positive impacts of human activity in mountainous regions have increased significantly.

As the mountains become more accessible, and as we learn to exploit their ecosystems for material development and benefits, it brings about a degradation of the natural environment. These delicate systems are being negatively impacted by an increase in local populations, as well as the large-scale annual migration of tourists and adventurers.

Once secluded areas are now opening to exploitation by industry and tourism. We should consider the lessons and history of Nepal’s own national development and that of our tourism industry.

The COVID-19 pandemic gives the mountains of Nepal a breathing space and it buys us time to chart a new course so that our development model does not come at the cost of irreversible natural degradation.

As previously remote and pristine areas are opened to human exploitation and activity, there is an increasingly urgent need to act to protect and nurture nature in the same manner that it has nurtured our people.

Growing up as a Sherpa boy in the then remote mountains of Solukhumbu, I have experienced the changes in these mountainous regions first-hand. Like the rest of the mountainous regions of Nepal, Gokyo Valley of Khumbu Pasanglhamu Rural Municipality #4, is being transformed by development.

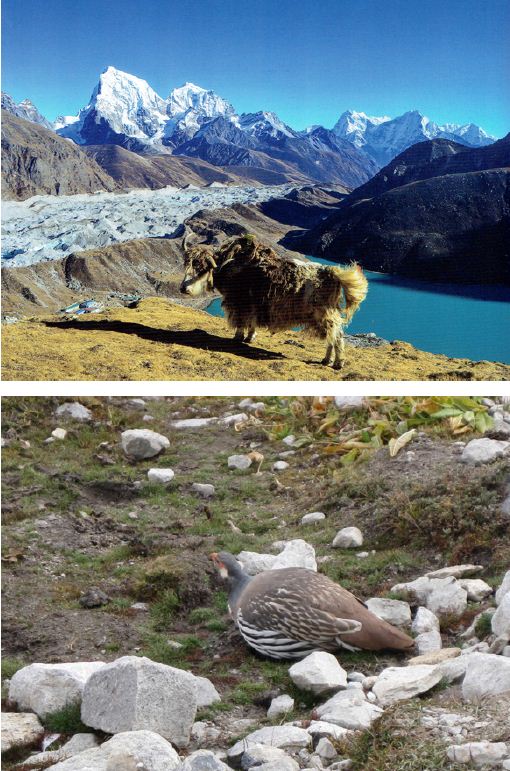

Thirty years ago, Gokyo valley along the Ngozumba Glacier, Nepal’s longest, was uninhabited except for the summer grazing of livestock. Gokyo also has religious significance, and has remained a sacred pilgrimage site for centuries.

The holy Gokyo Lakes at 4,750m-5,000m are popular pilgrimage destinations for both Hindus and Buddhists. During the Janai Purnima

Festival in mid-August, thousands of Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims flock to the holy site to bathe and renew themselves.

The spectacular blue lake was internationally designated as a Ramsar wetland preservation site in 2007. Gokyo is not only a destination for grazing yaks and spiritual pilgrimage, it is the home of many unique and rare species. The alpine biomes of the lakes support endangered and unique flora and fauna.

Endemic medicinal and aromatic plants species such as the flowering Kobresia fissiglumis or the medicinal kutki plant are a resource for local populations. While the ecosystem is delicate, it is able to support large mammals such as the Himalayan Tahr and the Snow Leopard.

The lakes are also an important stopover for birds on their trans-Himalayan migrations twice a year. Flocks of migratory ducks briefly join local birds such as the wood snipe on their way to and from the Tibetan Plateau and beyond.

However, during the last two decades, Gokyo Valley has become the second most popular remote destination among trekkers seeking adventure, challenges and solitude. The main attractions are the mountains all around from Cho Oyu that rises up at the head of the valley, to Mt Everest and Makalu to the east, and Thamserku and Kangtega to the south.

Many trekkers started making Gokyo their destination to avoid the crowds on the Everest Trail, and also because the view from Gokyo Ri is more spectacular. The Sagarmatha National Park received more than 60,000 tourists in 2019, and a third of them visited Gokyo.

When asked, trekkers cite several reasons for why they come to Gokyo. Many believe that the panorama from Kala Patar above Everest Base Camp is actually much more constricted by high mountains, and there are no human settlements in the upper Khumbu Glacier to give the human touch.

The other attractions of Gokyo were:

- Better perspective on Mt Everest by means of a shorter and more easily accomplished route

- More professional excursions to the lake and surrounding viewpoints

- Sherpa ancestral culture, traditional mountain villages and friendly homestays

- An overwhelming, inspiring and incredible landscape all along the trail as well as from Gokyo Ri

- Challenging walks and healthy activity

- Delicious, healthy and appetising local dishes and meals in Sherpa family lodgings

- The camaraderie and storytelling around the fire or stove

- Stunning sunsets

While the number of visitors to the Gokyo Valley is small compared to those visiting the Everest Base Camp their impact is nevertheless significant, and growing. Tourism in the Gokyo Valley has, without a doubt, provided a range of positive opportunities to the local people in the form of employment and income.

Gokyo Lake now faces the impact of livestock and pilgrims. These can be locally resolved and mitigated, but the increased volume of tourism and the higher material demands and consumption of tourists and adventurers is a threat to Gokyo’s fragile ecosystem.

The following quote from a local yak herder interviewed in 2013 explains the dilemma:

“My family has been coming to Gokyo for over four to five decades. In my father’s time, one goth had as many as 100 yaks and naks, but now no one has more than 1 or 2. People can’t keep up as many as they used to. There isn’t enough grass. The main reason is that the area has become a tourists hub. The goth has turned into teashops and lodges thereby increasing the number of teashops and lodges significantly within last two to three decades.”

Despite obvious problems caused by human activity, there continues to be a steady increase of herders, pilgrims and tourists in these areas. The delicate environment is struggling to cope, and the once productive pastures of the Gokyo Valley are degrading into scrubland.

As a result of this degradation of the ecosystem, the area is further compromised by deforestation and overgrazing. At these high altitudes, the loss of the delicate flora results in landslides and erosion, which adds to the rapid deterioration of the fragile mountain ecology.

Human waste is the other issue in Gokyo, as the number of tourists expands so does the support staff needed to take care of them. The tourists all expect western style bathrooms with flush toilets, showers and other facilities. The traditional pit latrines that used to provide manure for the fields have now been replaced with septic tanks, where the overflow feeds directly into the sacred lakes.

The traditional pit compost toilet is environmentally friendly and is a reasonable local solution. We have abandoned sustainable ancestral methods to modern sanitation facilities under the assumption that they are more modern and guests prefer them.

—

The primary reason for this situation is the family scale economic opportunity provided by tourism. Locals derive economic security from tourism, attracting yak herders and potato farmers to abandon their traditional lifestyle and expand into delicate wilderness areas to build more lodges.

Increase in tourism also means there is greater demand for energy. Cooking is mostly done with LPG cylinders that are brought up on yaks and mules from Phaplu. But the demand for firewood has meant that dwarf junipers growing along the Ngozumba moraine and shrubs on the slopes are being used up for cooking and heating.

As long as firewood demand was local and not very high, nature had a chance to grow back. But at higher altitudes, plant growth is much slower and the greater demand for firewood means the alpine vegetation does not have time to regenerate – resulting in the destruction of many years’ worth of growth in order to provide tourists with a hot shower or tea.

Unlike most of the high altitude wetlands and sacred lakes of Nepal, which have no nearby villages and are largely uninhabited, local seasonal herders and tourists trekking use Gokyo’s lake intensively.

Based upon my observations made in the Gokyo Valley, these are the environmental problems that the region is facing:

- Encroachment of the lakefront by lodges, walls and other construction

- Increased number of lodges surrounding lake

- Removal of cushion plants and rhododendron shrubs, thereby increasing siltation of the lake bed

- Plastic packaging and non-compostable garbage is being carried into the sacred lake by wind and rain

- Flush toilets using large amounts of water mixed with human waste eventually draining directly into the sacred lake

- Lack of management and few environmentally mitigating rules or instruction for pilgrims

- Erosion due to loss of vegetation cover on the moraine and slopes, and an increase in danger of landslides

- Geologically fragile mountain structure

- Continued retreat of the glaciers is resulting in the formation of new lakes

Indeed, aside from the short-term pressure from increased tourist traffic, the entire Khumbu region is feeling the direct impact of climate change The Gokyo lakes are expanding. Supraglacial lakes and meltpools on the debris-covered Ngozumba Glacier are expanding, as the glacier itself retreats and shrinks.

The ice is melting because the mountains are thawing at a faster rate than the global average. At present rates of warming, one-third of the remaining ice in the Himalaya is expected to melt by 2050 But aside from global temperature rise, the ice-fields higher up are also melting because of soot deposition from pollution and forest fires. This has accelerated the glacial retreat, and the trend can be seen all around Gokyo in the dirty ice.

—

All of these varied human activities are rapidly degrading depleting and altering the natural conditions of the regions’ resources. The extraction of these mountain resources has increased, yet there is little or no reinvestment into either the local ecology or local communities.

Investing in the stabilising and improving of the ecosystem as well as providing security to the local population are both equally necessary and have to happen side by side.

Those resources, which are extracted or utilised, should be managed in a manner that sustains the unique mountain environment and cultures, thereby preserving its many valuable potentials. In order to protect our precious resources, this threat of destruction by our own people and international visitors can and should be avoided.

This can be accomplished in part by the careful and considerate planning and implementation of local or national development projects. In order to achieve long-term management, Sagarmatha National Park must not forget to involve the local people from the very beginning and inception of any program or project that is to be considered.

It is now obvious that nature conservation is not possible with local participation. This has been demonstrated clearly in the many failed conservation projects and programs in Nepal and worldwide.

We must use the time we have been given by the coronavirus lockdown to think of a new way of managing tourism in Nepal in general, Solukhumbu in particular – and especially in the fragile Gokyo area if we are to protect this unique natural landscape for posterity:

- It is not wise, sustainable or recommended to construct hotels and lodges in one of the world’s finest unspoiled natural areas, without regard to their architectural suitability

- Local lodges along the main destinations are undergoing expansion and refurbishment without proper planning and minimal codes of conduct. To avoid further deterioration, there is an urgent need for a building code and the introduction of a permit system for new establishments

- Local participation in the planning and management of protected areas is desirable, a community-based approach to tourism is essential to boosting the local economy and ensures a more equitable distribution of the benefits. Local participation also greatly increases the community’s investment and cooperation with program or project goals

- There should be a regular monitoring system for tourist lodges and facilities and this system must be standardised as per Himalayan National Parks Rules and Regulations. All lodge operators should be given sufficient training in lodge management and related issues

- Establishment of a Lodge Management Committee could provide more democratic and effective control of this local economic activity. Likewise, committees can play a key role in promoting fuel-efficient technologies, proper waste management, fixing and improving menus based upon geographical pricing systems, standardising lodges, promoting improved sanitation and hygiene conditions, as well as the building and maintaining of community trails

This article appeared in Nepali Times Magazine on June 27, 2020